Some parts of H.264 Column (English Version)

Index

- Video coding with H.264/AVC: Tools, Performance and Complexity

2. Concept of Standardized Video Coding Schemes

3. The H.264/AVC Coding Scheme

3.1 Intra Prediction

3.2 Motion Compensated Prediction

3.3 Transform Coding

3.4 Entropy Coding Schemes

3.5 Adaptive Deblocking Filter

3.6 Error Robustness and Network Friendliness - References

Main

References of Column

Video coding with H.264/AVC: Tools, Performance and Complexity

2. Concept of Standardized Video Coding Schemes

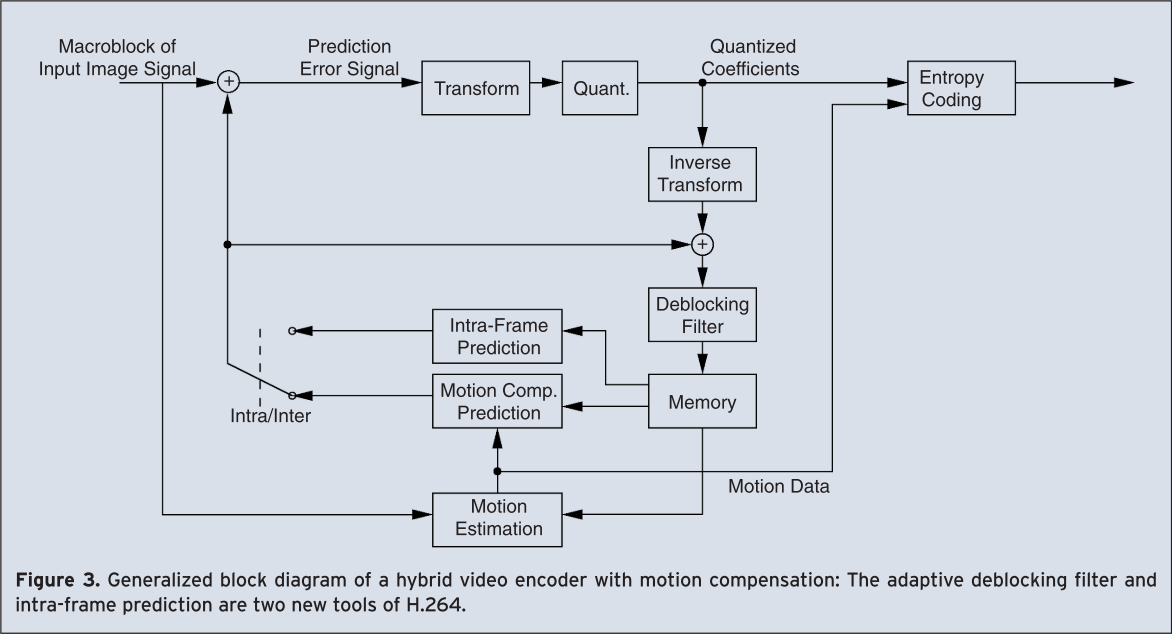

Standardized video coding techniques like H.263, H.264/AVC, MPEG-1, 2, 4 are based on hybrid video coding. Figure 3 shows the generalized block diagram of such a hybrid video encoder.

The input image is divided into macroblocks. Each macroblock consists of the three components Y, Cr and Cb. Y is the luminance component which represents the brightness information. Cr and Cb represent the color information. Due to the fact that the human eye system is less sensitive to the chrominance than to the luminance the chrominance signals are both subsampled by a factor of 2 in horizontal and vertical direction. Therefore, a macroblock consists of one block of 16 by 16 picture elements for the luminance component and of two blocks of 8 by 8 picture elements for the color components.

These macroblocks are coded in Intra or Inter mode. In Inter mode, a macroblock is predicted using motion compensation. For motion compensated prediction a displacement vector is estimated and transmitted for each block (motion data) that refers to the corresponding position of its image signal in an already transmitted reference image stored in memory. In Intra mode, former standards set the prediction signal to zero such that the image can be coded without reference to previously sent information. This is important to provide for error resilience and for entry points into the bit streams enabling random access. The prediction error, which is the difference between the original and the predicted block, is transformed, quantized and entropy coded. In order to reconstruct the same image on the decoder side, the quantized coefficients are inverse transformed and added to the prediction signal. The result is the reconstructed macroblock that is also available at the decoder side. This macroblock is stored in a memory. Macroblocks are typically stored in raster scan order.

With respect to this simple block diagram (Figure 3), H.264/AVC introduces the following changes:

- In order to reduce the block-artifacts an adaptive deblocking filter is used in the prediction loop. The deblocked macroblock is stored in the memory and can be used to predict future macroblocks.

- Whereas the memory contains one video frame in previous standards, H.264/AVC allows storing multiple video frames in the memory.

- In H.264/AVC a prediction scheme is used also in Intra mode that uses the image signal of already transmitted macroblocks of the same image in order to predict the block to code.

- The Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) used in former standards is replaced by an integer transform.

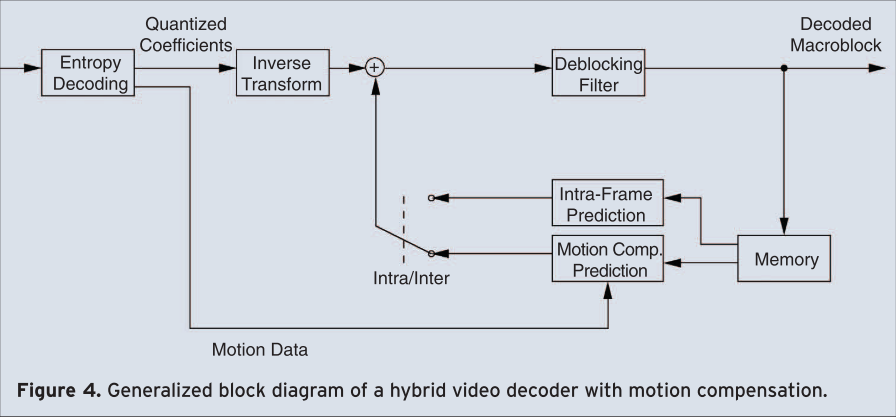

Figure 4 shows the generalized block diagram of the corresponding decoder. The entropy decoder decodes the quantized coefficients and the motion data, which is used for the motion compensated prediction. As in the encoder, a prediction signal is obtained by intra-frame or motion compensated prediction, which is added to the inverse transformed coefficients. After deblocking filtering, the macroblock is completely decoded and stored in the memory for further predictions.

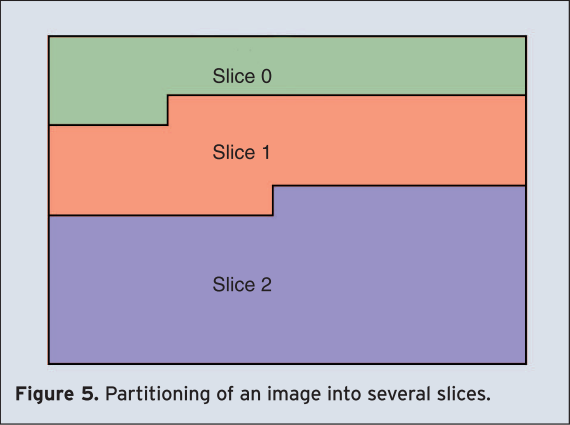

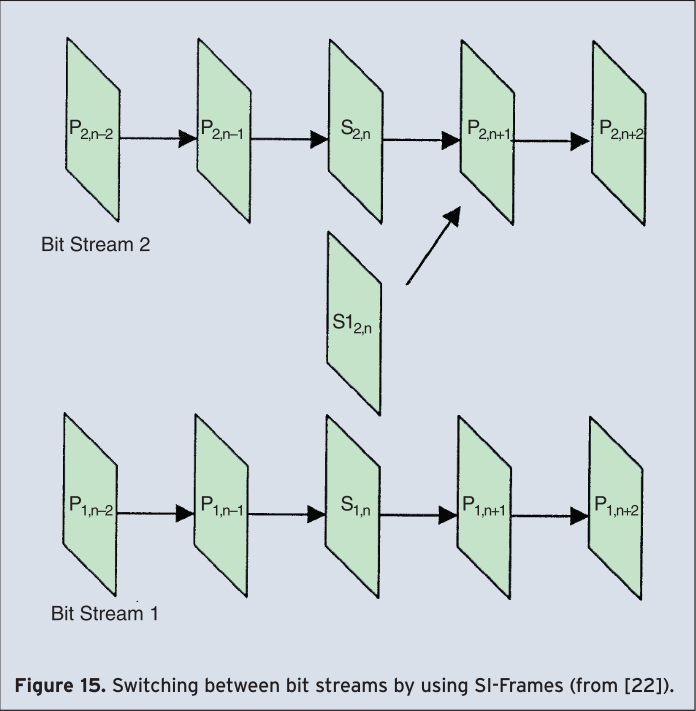

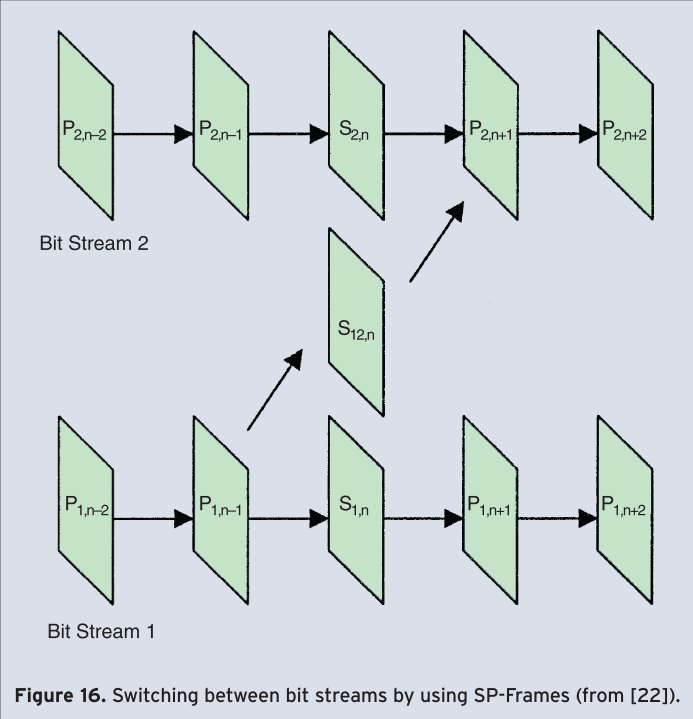

In H.264/AVC, the macroblocks are processed in so called slices whereas a slice is usually a group of macroblocks processed in raster scan order (see Figure 5). In special cases, which will be discussed in Section 3.6, the processing can differ from the raster scan order. Five different slice-types are supported which are I-, P-, B-, SI- and SP-slices. In an I-slice, all macroblocks are encoded in Intra mode. In a P-slice, all macroblocks are predicted using a motion compensated prediction with one reference frame and in a B-slice with two reference frames. SI- and SP-slices are specific slices that are used for an efficient switching between two different bitstreams. They are both discussed in Section 3.6.

For the coding of interlaced video, H.264/AVC supports two different coding modes. The first one is called frame mode. In the frame mode, the two fields of one frame are coded together as if they were one single progressive frame. The second mode is called field mode. In this mode, the two fields of a frame are encoded separately. These two different coding modes can be selected for each image or even for each macroblock. If they are selected for each image, the coding is referred to as picture adaptive field/frame coding (P-AFF). Whereas MPEG-2 allows for selecting the frame/field coding on a macroblock level H.264 allow for selecting this mode on a vertical macroblock pair level. This coding is referred to as macroblock-adaptive frame/field coding (MB-AFF). The choice of the frame mode is efficient for regions that are not moving. In non-moving regions there are strong statistical dependencies between adjacent lines even though these lines belong to different fields. These dependencies can be exploited in the frame mode. In the case of moving regions the statistical dependencies between adjacent lines are much smaller. It is more efficient to apply the field mode and code the two fields separately.

3. The H.264/AVC Coding Scheme

In this Section, we describe the tools that make H.264 such a successful video coding scheme. We discuss Intra coding, motion compensated prediction, transform coding, entropy coding, the adaptive deblocking filter as well as error robustness and network friendliness.

3.1 Intra Prediction

Intra prediction means that the samples of a macroblock are predicted by using only information of already transmitted macroblocks of the same image. In H.264/AVC, two different types of intra prediction are possible for the prediction of the luminance component Y.

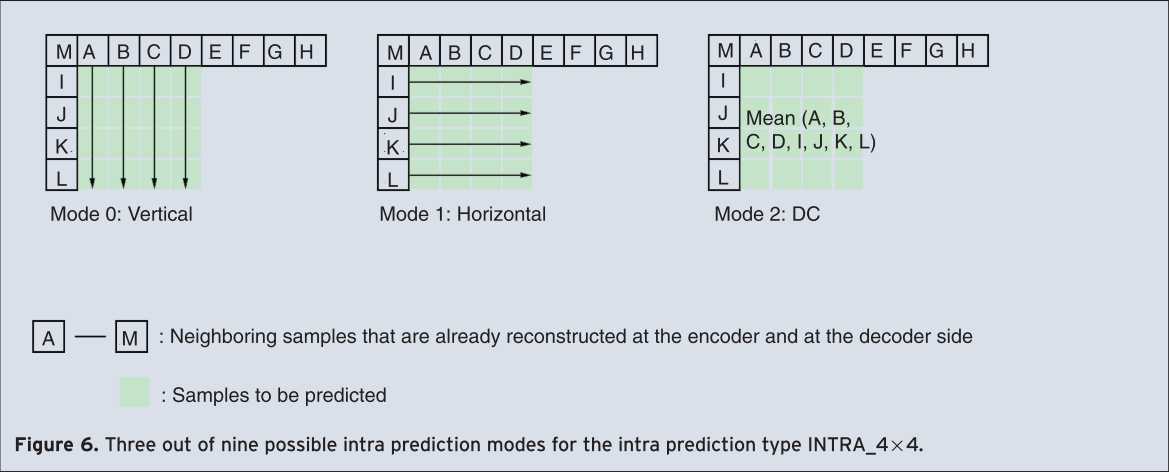

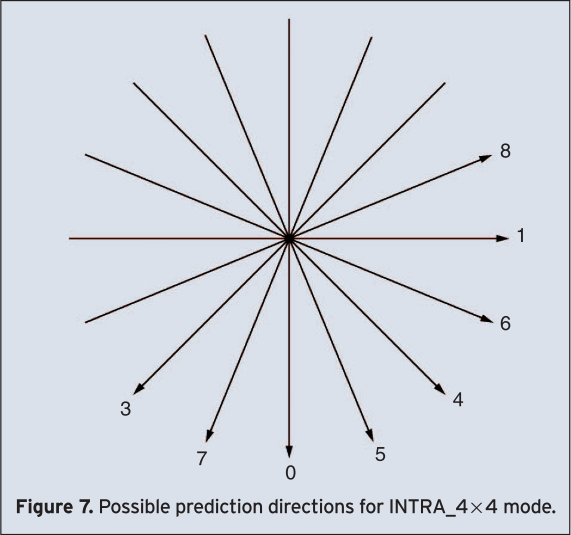

The first type is called INTRA_4×4 and the second one INTRA_16×16. Using the INTRA_4×4 type, the macroblock, which is of the size 16 by 16 picture elements (16×16), is divided into sixteen 4×4 subblocks and a prediction for each 4×4 subblock of the luminance signal is applied individually. For the prediction purpose, nine different prediction modes are supported. One mode is DC-prediction mode, whereas all samples of the current 4×4 subblock are predicted by the mean of all samples neighboring to the left and to the top of the current block and which have been already reconstructed at the encoder and at the decoder side (see Figure 6, Mode 2). In addition to DC-prediction mode, eight prediction modes each for a specific prediction direction are supported. All possible directions are shown in Figure 7. Mode 0 (vertical prediction) and Mode 1 (horizontal prediction) are shown explicitly in Figure 6. For example, if the vertical prediction mode is applied all samples below sample A (see Figure 6) are predicted by sample A, all samples below sample B are predicted by sample B and so on.

Using the type INTRA_16×16, only one prediction mode is applied for the whole macroblock. Four different prediction modes are supported for the type INTRA_16×16: Vertical prediction, horizontal prediction, DC-prediction and plane-prediction. Hereby plane-prediction uses a linear function between the neighboring samples to the left and to the top in order to predict the current samples. This mode works very well in areas of a gently changing luminance. The mode of operation of these modes is the same as the one of the 4×4 prediction modes. The only difference is that they are applied for the whole macroblock instead of for a 4×4 subblock. The efficiency of these modes is high if the signal is very smooth within the macroblock.

The intra prediction for the chrominance signals Cb and Cr of a macroblock is similar to the INTRA_16×16 type for the luminance signal because the chrominance signals are very smooth in most cases. It is performed always on 8×8 blocks using vertical prediction, horizontal prediction, DC-prediction or plane-prediction. All intra prediction modes are explained in detail in [1].

3.2 Motion Compensated Prediction

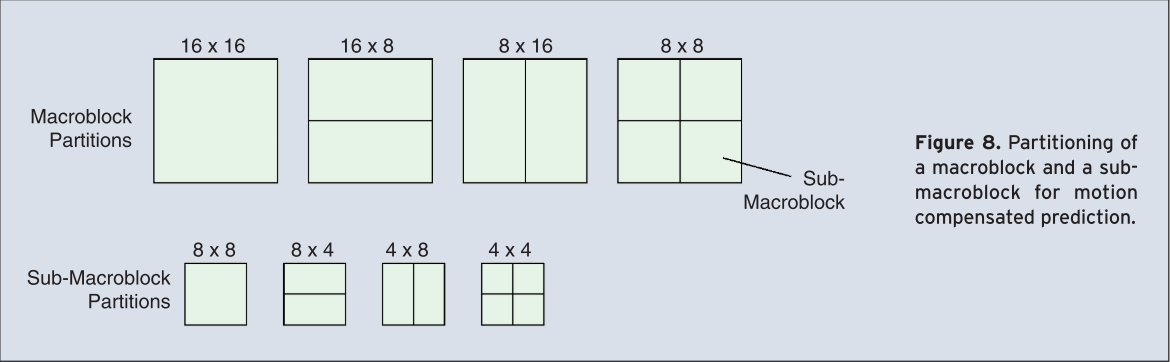

In case of motion compensated prediction macroblocks are predicted from the image signal of already transmitted reference images. For this purpose, each macroblock can be divided into smaller partitions. Partitions with luminance block sizes of 16×16, 16×8, 8×16, and 8×8 samples are supported. In case of an 8×8 sub-macroblock in a P-slice, one additional syntax element specifies if the corresponding 8×8 sub-macroblock is further divided into partitions with block sizes of 8×4, 4×8 or 4×4[8]. The partitions of a macroblock and a sub-macroblock are shown in Figure 8.

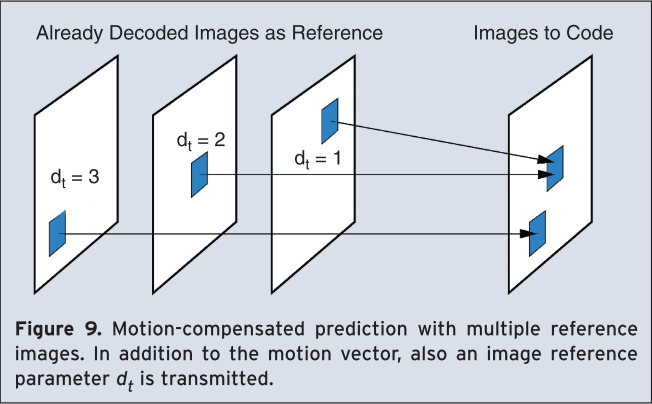

In former standards as MPEG-4 or H.263, only blocks of the size 16×16 and 8×8 are supported. A displacement vector is estimated and transmitted for each block, refers to the corresponding position of its image signal in an already transmitted reference image. In former MPEG standards this reference image is the most recent preceding image. In H.264/AVC it is possible to refer to several preceding images. For this purpose, an additional picture reference parameter has to be transmitted together with the motion vector. This technique is denoted as motion-compensated prediction with multiple reference frames [9]. Figure 9 illustrates the concept that is also extended to B-slices.

The accuracy of displacement vectors is a quarter of a picture element (quarter-pel or 1/4-pel). Such displacement vectors with fractional-pel resolution may refer to positions in the reference image, which are spatially located between the sampled positions of its image signal. In order to estimate and compensate fractional-pel displacements, the image signal of the reference image has to be generated on sub-pel positions by interpolation. In H.264/AVC the luminance signal at half-pel positions is generated by applying a one-dimensional 6-tap FIR filter, which was designed to reduce aliasing components that deteriorate the interpolation and the motion compensated prediction [8]. By averaging the luminance signal at integer- and half-pel positions the image signal at quarter-pel positions is generated. The chrominance signal at all fractional-pel positions is obtained by averaging.

In comparison to prior video-coding standards, the classical concept of B-pictures is extended to a generalized B-slice concept in H.264/AVC. In the classical concept, B-pictures are pictures that are encoded using both past and future pictures as references. The prediction is obtained by a linear combination of forward and backward prediction signals. In former standards, this linear combination is just an averaging of the two prediction signals whereas H.264/AVC allows arbitrary weights. In this generalized concept, the linear combination of prediction signals is also made regardless of the temporal direction. For example, a linear combination of two forward-prediction signals may be used (see Figure 9). Furthermore, using H.264/AVC it is possible to use images containing B-slices as reference images for further predictions which was not possible in any former standard. Details on this generalized B-slice concept, which is also known as multi-hypothesis motion-compensated prediction can be found in [10], [11], [12].

3.3 Transform Coding

Similar to former standards transform coding is applied in order to code the prediction error signal. The task of the transform is to reduce the spatial redundancy of the prediction error signal. For the purpose of transform coding, all former standards such as MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 applied a two dimensional Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) [13] of the size 8×8. Instead of the DCT, different integer transforms are applied in H.264/AVC. The size of these transforms is mainly 4×4, in special cases 2×2. This smaller block size of 4×4 instead of 8×8 enables the encoder to better adapt the prediction error coding to the boundaries of moving objects, to match the transform block size with the smallest block size of the motion compensation, and to generally better adapt the transform to the local prediction error signal.

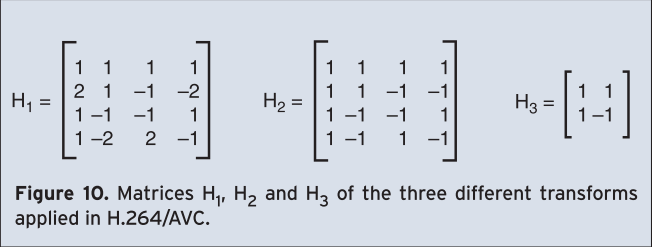

Three different types of transforms are used. The first type is applied to all samples of all prediction error blocks of the luminance component Y and also for all blocks of both chrominance components Cb and Cr regardless of whether motion compensated prediction or intra prediction was used. The size of this transform is 4×4. Its transform matrix \( \mathrm{H_1} \) is shown in Figure 10.

If the macroblock is predicted using the type INTRA_16×16, the second transform, a Hadamard transform with matrix \( \mathrm{H_2} \) (see Figure 10), is applied in addition to the first one. It transforms all 16 DC coefficients of the already transformed blocks of the luminance signal. The size of this transform is also 4×4.

The third transform is also a Hadamard transform but of size 2×2. It is used for the transform of the 4 DC coefficients of each chrominance component. Its matrix \( \mathrm{H_3} \) is shown in Figure 10.

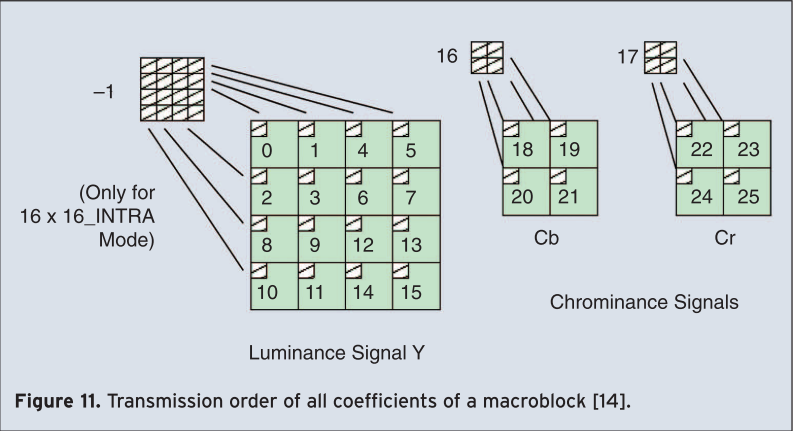

The transmission order of all coefficients is shown in Figure 11. If the macroblock is predicted using the intra prediction type INTRA_16×16 the block with the label “-1” is transmitted first. This block contains the DC coefficients of all blocks of the luminance component. Afterwards all blocks labeled “0”-“25” are transmitted whereas blocks “0”-“15” comprise all AC coefficients of the blocks of the luminance component. Finally, blocks “16” and “17” comprise the DC coefficients and blocks “18”-“25” the AC coefficients of the chrominance components.

Compared to a DCT, all applied integer transforms have only integer numbers ranging from -2 to 2 in the transform matrix (see Figure 10). This allows computing the transform and the inverse transform in 16-bit arithmetic using only low complex shift, add, and subtract operations. In the case of a Hadamard transform, only add and subtract operations are necessary. Furthermore, due to the exclusive use of integer operations mismatches of the inverse transform are completely avoided which was not the case in former standards and caused problems.

All coefficients are quantized by a scalar quantizer. The quantization step size is chosen by a so called quantization parameter QP which supports 52 different quantization parameters. The step size doubles with each increment of 6 of QP. An increment of QP by 1 results in an increase of the required data rate of approximately 12.5%. The transform is explained in detail in [15].

3.4 Entropy Coding Schemes

H.264/AVC specifies two alternative methods of entropy coding: a low-complexity technique based on the usage of context-adaptively switched sets of variable length codes, so-called CAVLC, and the computationally more demanding algorithm of context-based adaptive binary arithmetic coding (CABAC). Both methods represent major improvements in terms of coding efficiency compared to the techniques of statistical coding traditionally used in prior video coding standards. In those earlier methods, specifically tailored but fixed variable length codes (VLCs) were used for each syntax element or sets of syntax elements whose representative probability distributions were assumed to be closely matching. In any case, it was implicitly assumed that the underlying statistics are stationary, which however in practice is seldom the case. Especially residual data in a motion-compensated predictive coder shows a highly non-stationary statistical behavior, depending on the video content, the coding conditions and the accuracy of the prediction model. By incorporating context modeling in their entropy coding framework, both methods of H.264/AVC offer a high degree of adaptation to the underlying source, even though at a different complexity-compression trade-off.

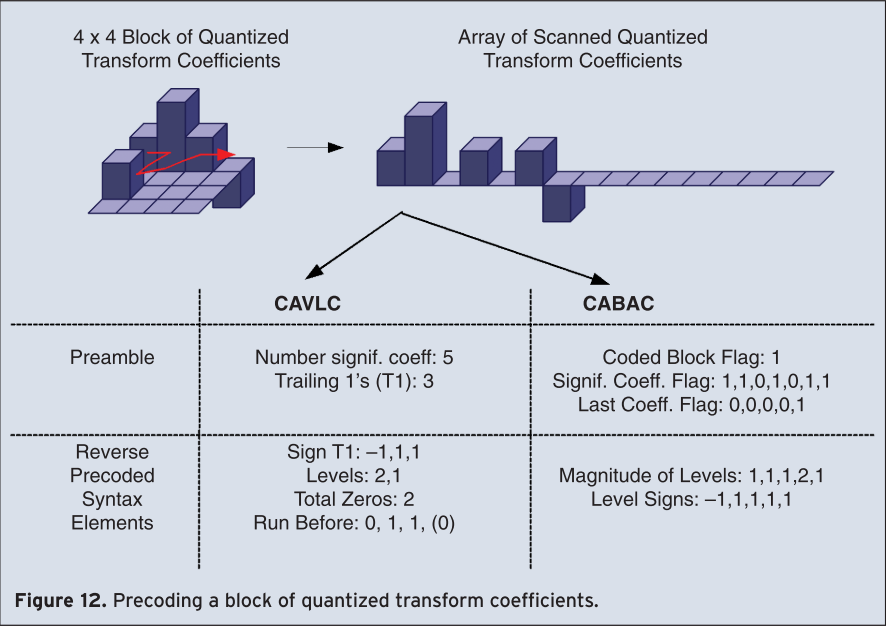

CAVLC is the baseline entropy coding method of H.264/AVC. Its basic coding tool consists of a single VLC of structured Exp-Golomb codes, which by means of individually customized mappings is applied to all syntax elements except those related to quantized transform coefficients. For the latter, a more sophisticated coding scheme is applied. As shown in the example of Figure 12, a given block of transform coefficients is first mapped on a 1-D array according to a predefined scanning pattern. Typically, after quantization a block contains only a few significant, i.e., nonzero coefficients, where, in addition, a predominant occurrence of coefficient levels with magnitude equal to 1, so-called trailing 1’s (T1), is observed at the end of the scan. Therefore, as a preamble, first the number of nonzero coefficients and the number of T1s are transmitted using a combined codeword, where one out of four VLC tables are used based on the number of significant levels of neighboring blocks. Then, in the second step, sign and level value of significant coefficients are encoded by scanning the list of coefficients in revers order. By doing so, the VLC for coding each individual level value is adapted on the base of the previously encoded level by choosing among six VLC tables. Finally, the zero quantized coefficients are signaled by transmitting the total number of zeros before the last nonzero level for each block, and additionally, for each significant level the corresponding run, i.e., the number of consecutive preceding zeros. By monitoring the maximum possible number of zeros at each coding stage, a suitable VLC is chosen for the coding of each run value. A total number of 32 different VLCs are used in CAVLC entropy coding mode, where, however, the structure of some of these VLCs enables simple on-line calculation of any code word without recourse to the storage of code tables. For typical coding conditions and test material, bit rate reductions of 2–7% are obtained by CAVLC relative to a conventional run-length scheme based on a single Exp-Golomb code.

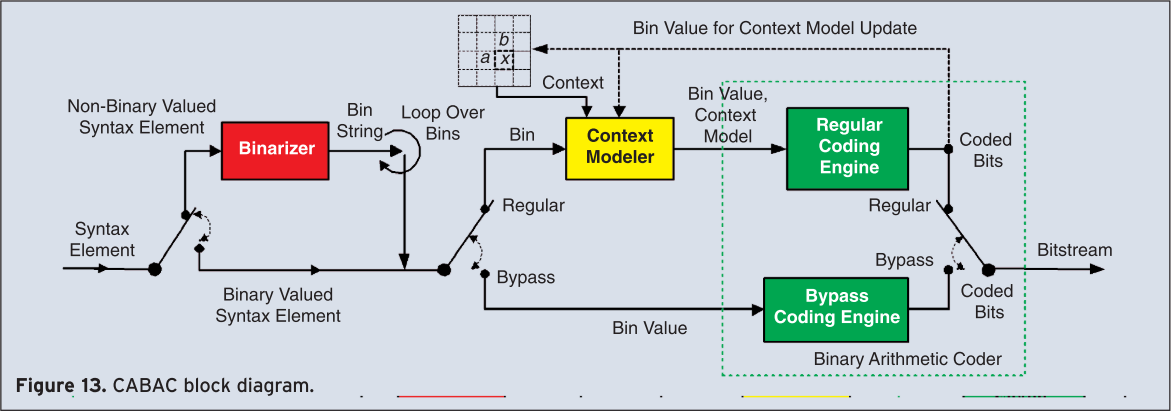

For significantly improved coding efficiency, CABAC as the alternative entropy coding mode of H.264/AVC is the method of choice (Figure 13). As shown in Figure 13, the CABAC design is based on the key elements: binarization, context modeling, and binary arithmetic coding. Binarization enables efficient binary arithmetic coding via a unique mapping of non-binary syntax elements to a sequence of bits, a so-called bin string. Each element of this bin string can either be processed in the regular coding mode or the bypass mode. The latter is chosen for selected bins such as for the sign information or lower significant bins, in order to speedup the whole encoding (and decoding) process by means of a simplified coding engine bypass. The regular coding mode provides the actual coding benefit, where a bin may be context modeled and subsequently arithmetic encoded. As a design decision, in general only the most probable bin of a syntax element is supplied with a context model using previously encoded bins. Moreover, all regular encoded bins are adapted by estimating their actual probability distribution. The probability estimation and the actual binary arithmetic coding is conducted using a multiplication-free method that enables efficient implementations in hardware and software. Note that for coding of transform coefficients, CABAC is applied to specifically designed syntax elements, as shown in the example of Figure 12. Typically, CABAC provides bit rate reductions of 5–15% compared to CAVLC. More details on CABAC can be found in [16].

3.5 Adaptive Deblocking Filter

The block-based structure of the H.264/AVC architecture containing 4×4 transforms and block-based motion compensation, can be the source of severe blocking artifacts. Filtering the block edges has been shown to be a powerful tool to reduce the visibility of these artifacts. Deblocking can in principle be carried out as post-filtering, influencing only the pictures to be displayed. Higher visual quality can be achieved though, when the filtering process is carried out in the coding loop, because then all involved past reference frames used for motion compensation will be the filtered versions of the reconstructed frames. Another reason to make deblocking a mandatory in-loop tool in H.264/AVC is to enforce a decoder to approximately deliver a quality to the customer, which was intended by the producer and not leaving this basic picture enhancement tool to the optional good will of the decoder manufacturer.

The filter described in the H.264/AVC standard is highly adaptive. Several parameters and thresholds and also the local characteristics of the picture itself control the strength of the filtering process. All involved thresholds are quantizer dependent, because blocking artifacts will always become more severe when quantization gets coarse.

H.264/MPEG-4 AVC deblocking is adaptive on three levels:

- On slice level, the global filtering strength can be adjusted to the individual characteristics of the video sequence.

- On block edge level, the filtering strength is made dependent on inter/intra prediction decision, motion differences, and the presence of coded residuals in the two participating blocks. From these variables a filtering-strength parameter is calculated, which can take values from 0 to 4 causing modes from no filtering to very strong filtering of the involved block edge.

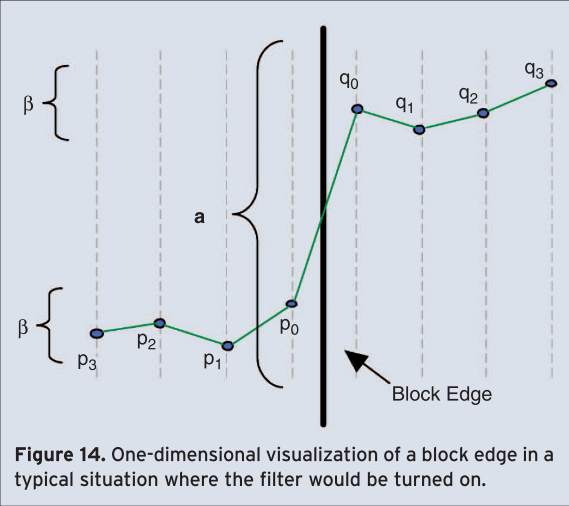

- On sample level, it is crucially important to be able to distinguish between true edges in the image and those created by the quantization of the transform-coefficients. True edges should be left unfiltered as much as possible. In order to separate the two cases, the sample values across every edge are analyzed. For an explanation denote the sample values inside two neighboring 4×4 blocks as \( \mathrm{p_3,\ p_2,\ p_1,\ p_0\ |\ q_0,\ q_1,\ q_2,\ q_3} \) with the actual boundary between \( \mathrm{p_0} \) and \( \mathrm{q_0} \) as shown in Figure 14. Filtering of the two pixels \( \mathrm{p_0} \) and \( \mathrm{q_0} \) only takes place, if their absolute difference falls below a certain threshold \( \alpha \). At the same time, absolute pixel differences on each side of the edge ( \( \mathrm{|p_1 - p_0|} \) and \( \mathrm{|q_1 - q_0|} \) ) have to fall below another threshold \( \beta \), which is considerably smaller than \( \alpha \). To enable filtering of \( \mathrm{p_1 ( q_1 )} \), additionally the absolute difference between \( \mathrm{p_0} \) and \( \mathrm{p_2} \) ( \( \mathrm{q_0} \) and \( \mathrm{q_2} \) ) has to be smaller than \( \beta \). The dependency of \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \) on the quantizer, links the strength of filtering to the general quality of the reconstructed picture prior to filtering. For small quantizer values the thresholds both become zero, and filtering is effectively turned off altogether.

All filters can be calculated without multiplications or divisions to minimize the processor load involved in filtering. Only additions and shifts are needed. If filtering is turned on for p0, the impulse response of the involved filter would in principle be \( (0,\ 1,\ 4,\ |\ 4,\ -1,\ 0)\ /\ 8 \). For \( p_1 \) it would be \( (4,\ 0,\ 2,\ |\ 2,\ 0,\ 0)\ /\ 8 \). The term in principle means that the maximum changes allowed for \( \mathrm{p_0} \) and \( \mathrm{p_1} \) ( \( \mathrm{q_0} \) and \( \mathrm{q_1} \) ) are clipped to relatively small quantizer dependent values, reducing the low pass characteristic of the filter in a nonlinear manner.

Intra coding in H.264/AVC tends to use INTRA_16×16 prediction modes when coding nearly uniform image areas. This causes small amplitude blocking artifacts at the macro block boundaries which are perceived as abrupt steps in these cases. To compensate the resulting tiling artifacts, very strong low pass filtering is applied on boundaries between two macro blocks with smooth image content. This special filter also involves pixels \( \mathrm{p_3} \) and \( \mathrm{q_3} \).

In general deblocking results in bit rate savings of around 6-9% at medium qualities. More remarkable are the improvements in subjective picture quality. A more concise description of the H.264/AVC deblocking scheme can be found in [17].

3.6 Error Robustness and Network Friendliness

For efficient transmission in different environments, the seamless and easy integration of the coded video into all current and future protocol and network architectures is important. Therefore, both the VCL and the NAL are part of the H.264/AVC standard (Figure 2). The VCL specifies an efficient representation for the coded video signal. The NAL defines the interface between the video codec itself and the outside world. It operates on NAL units which give support to the packet-based approach of most existing networks. In addition to the NAL concept, the VCL itself includes several features providing network friendliness and error robustness being essential especially for real-time services such as streaming, multicasting, and conferencing applications due to online transmission and decoding. The H.264/AVC Hypothetical Reference Decoder (HRD) [18] places constraints on encoded NAL unit streams in order to enable cost-effective decoder implementations by introducing a multiple-leaky-bucket model.

Lossy and variable bit rate (VBR) channels such as the Internet or wireless links require channel-adaptive streaming or multi-casting technologies. Among others [19], channel-adaptive packet dependency control [20] and packet scheduling [21] allow reacting to these channels when transmitting pre-encoded video streams. These techniques are supported in H.264/AVC by various means, namely frame dropping of non-reference frames resulting in well-known temporal scalability, the multiple reference frame concept in combination with generalized B-pictures allowing a huge flexibility on frame dependencies to be exploited for temporal scalability and rate shaping of encoded video, and the possibility of switching between different bit streams which are encoded at different bit rates. This technique is called version switching. It can be applied at Instantaneous Decoder Refresh (IDR) frames, or, even more efficiently by the usage of switching pictures which allow identical reconstruction of frames even when different reference frames are being used. Thereby, switching-predictive (SP) pictures efficiently exploit motion-compensated prediction whereas switching-intra (SI) pictures can exactly reconstruct SP pictures. The switching between two bit streams using SI and SP pictures is illustrated in Figure 15 and Figure 16. Switching pictures can also be applied for error resilience purposes as well as other features, for details see [22].

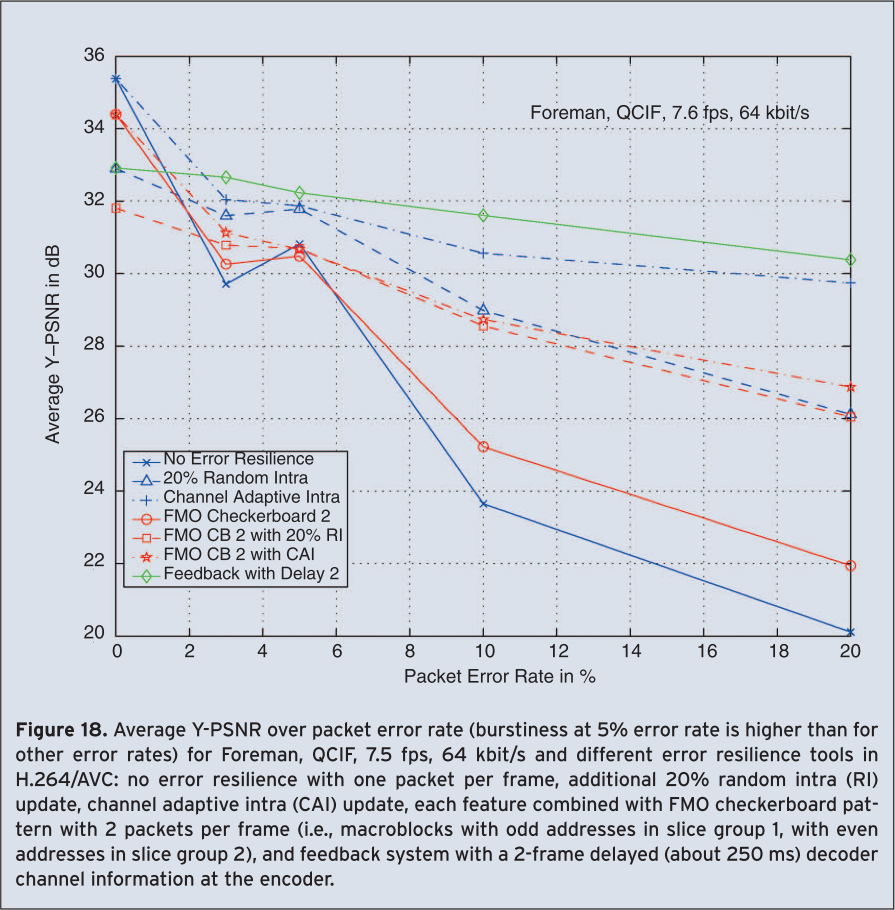

Whereas for relaxed-delay applications such as download-and-play, streaming, and broadcast/multicast, residual errors can usually be avoided by applying powerful forward error correction and retransmission protocols, the low delay requirements for conversational applications impose additional challenges as transmission errors due to congestions and link-layer imperfectness can generally not be avoided. Therefore, these video applications require error resilience features. The H.264/AVC standardization process acknowledged thisby adopting a set of common test conditions for IP based transmission [23]. Anchor video sequences, appropriate bit rates and evaluation criteria are specified. In the following we briefly present different error resilience features included in the standard, for more details we refer to [24] and [7]. The presentation is accompanied by Figure 18 showing results for a representative selection of the common Internet test conditions, namely for the QCIF sequence Foreman 10 seconds are encoded at a frame rate of 7.5 fps applying only temporally backward referencing motion compensation. The resulting total bit rate including a 40 byte IP/UDP/RTP header matches exactly 64 kbit/s. As performance measure the average luminance peak signal to noise ratio (PSNR) is chosen and sufficient statistics are obtained by transmitting at least 10000 data packets for each experiment as well as applying a simple packet loss simulator and Internet error patterns as specified in [23].

Although common understanding usually assumes that increased compression efficiency decreases error resilience, the opposite is the case if applied appropriately. As higher compression allows using additional bit rate for forward error correction, the loss probability of highly compressed data can be reduced assuming a constant overall bit rate. All other error resilience tools discussed in the following generally increase the data rate at the same quality, and, therefore, their application should always be considered very carefully in order not to effect adversely compression efficiency, especially if lower layer error protection is applicable. This can be seen for packet error rate 0 in Figure 18. Slice structured coding reduces packet loss probability and the visual degradation from packet losses, especially in combination with advanced decoder error concealment methods [25]. A slice is a sequence of macroblocks within one slice group and provides spatially distinct resynchronization points within the video data for a single frame. No intra-frame prediction takes place across slice boundaries. However, the loss of intra-frame prediction and the increased overhead associated with decreasing slice sizes adversely affect coding performance. Especially for wireless transmission a careful selection of the packet size is necessary [7].

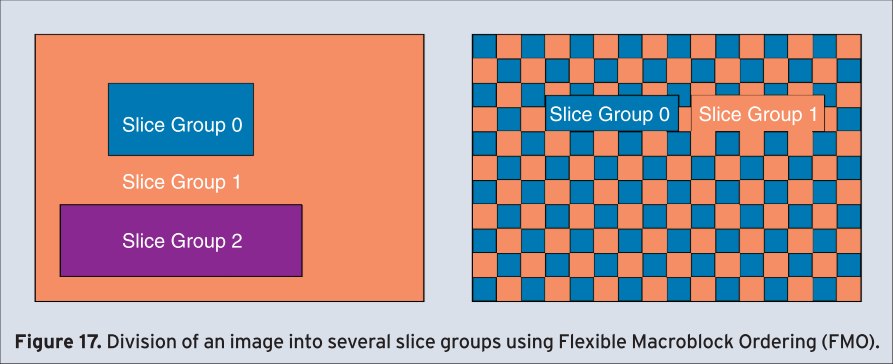

As a more advanced feature, Flexible Macroblock Ordering (FMO) allows the specification of macroblock allocation maps defining the mapping of macroblocks to slice groups, where a slice group itself may contain several slices. An example is shown in Figure 17.

Therefore, macroblocks might be transmitted out of raster scan order in a flexible and efficient way. Specific macroblock allocation maps enable the efficient application of features such as slice interleaving, dispersed macroblock allocation using checkerboard-like patterns, one or several foreground slice groups and one left-over background slice groups, or sub-pictures within a picture to support, e.g., isolated regions [26]. Figure 18 shows increased performance for FMO with checkerboard pattern for increasing error rate when compared to the abandoning of error resilience features.

Arbitrary slice ordering (ASO) allows that the decoding order of slices within a picture may not follow the constraint that the address of the first macroblock within a slice is monotonically increasing within the NAL unit stream for a picture. This permits, for example, to reduce decoding delay in case of out-of-order delivery of NAL units.

Data Partitioning allows up to three partitions for the transmission of coded information. Rather than just providing two partitions, one for the header and the motion information, and one for the coded transform coefficients, H.264/AVC can generate three partitions by separating the second partition in intra and inter information. This allows assigning higher priority to, in general, more important intra information. Thus, it can reduce visual artifacts resulting from packet losses, especially if prioritization or unequal error protection is provided by the network.

If despite of all these techniques, packet losses and spatio-temporal error propagation are not avoidable, quick recovery can only be achieved when image regions are encoded in Intra mode, i.e., without reference to a previously coded frame. H.264/AVC allows encoding of single macroblocks for regions that cannot be predicted efficiently. This feature can also be used to limit error propagation by transmitting a number of intra coded macroblocks anticipating transmission errors. The selection of Intra coded MBs can be done either randomly, in certain update patterns, or preferably in channel-adaptive rate-distortion optimized way [7], [27]. Figure 18 reveals that the introduction of intra coded macroblocks significantly improves the performance for increased error rates and can be combined with any aforementioned error resilience features. Thereby, channel-adaptive intra updates can provide better results than purely random intra updates, especially over the entire range of error rates.

A redundant coded slice is a coded slice that is a part of a redundant picture which itself is a coded representation of a picture that is not used in the decoding process if the corresponding primary coded picture is correctly decoded. Examples of applications and coding techniques utilizing the redundant coded picture feature include the video redundancy coding [28] and protection of “key pictures” in multicast streaming [29].

In bi-directional conversational applications it is common that the encoder has the knowledge of experienced NAL unit losses at the decoder, usually with a small delay. This small information can be conveyed from the decoder to the encoder. Although retransmissions are not feasible in a low-delay environment, this information is still useful at the encoder to limit error propagation [30]. The flexibility provided by the multiple reference frame concept in H.264/AVC allows incorporating so called NEWPRED approaches [31] in a straight-forward manner which address the problem of error propagation. For most successful applications, a selection of reference frames and intra updates can be integrated in a rate-distortion optimized encoder control as discussed in Section 4 taking into account not only video statistics, but also all available channel information [7]. Excellent results are shown in Figure 18 applying five reference frames and feedback delay of two frames, especially for moderate to higher error rates. To improve the performance also for low error rates, a combination of channel adaptive intra updates and feedback might be considered according to [27] at the expense of increased encoding complexity.

References

Main

References of Column

[1] ISO/IEC 14496–10:2003, “Coding of Audiovisual Objects—Part 10: Advanced Video Coding,” 2003, also ITU-T Recommendation H.264 “Advanced video coding for generic audiovisual services.”

[7] T. Stockhammer, M.M. Hannuksela, and T. Wiegand, “H.264/AVC in wireless environments,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 657–673, July 2003.

[8] T. Wedi and H.G. Musmann, “Motion and aliasing-compensated prediction for hybrid video coding,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, vol. 13, pp. 577–587, July 2003.

[9] T. Wiegand, X. Zhang, and B. Girod, “Long-term memory motion-compensated prediction for video coding,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol., vol. 9, pp. 70–84, Feb. 1999.

[10] T. Wiegand, H. Schwarz, A. Joch, and F. Kossentini, “Rate-constrained coder control and comparison of video coding standards,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, vol. 13, pp. 688–703, July 2003.

[11] B. Girod, “Efficiency analysis of multihypothesis motion-compensated prediction for video coding,” IEEE Trans. Image Processing, vol. 9, Feb. 1999.

[12] M. Flierl, T. Wiegand, and B. Girod, “Rate-constrained multi-hypothesis motion-compensated prediction for video coding,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Image Processing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, Sept. 2000, vol. 3, pp. 150–153.

[13] N. Ahmed, T. Natarajan, and R. Rao, “Discrete cosine transform,” IEEE Transactions on Computers, vol. C-23, pp. 90–93, Jan. 1974.

[15] H. Malvar, A. Hallapuro, M. Karczewicz, and L. Kerofsky, “Low-Complexity transform and quantization in H.264/AVC,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, vol. 13, pp. 598–603, July 2003.

[16] D. Marpe, H. Schwarz, and T. Wiegand, “Context-based adaptive binary arithmetic coding in the H.264/AVC video compression standard,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, vol. 13, pp. 620–636, July 2003.

[17] P. List, A. Joch, J. Lainema, and G. Bjontegaard, “Adaptive deblocking filter” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, vol. 13, pp. 614–619, July 2003.

[18] J. Ribas-Corbera, P.A. Chou, and S. Regunathan, “A generalized hypothetical reference decoder for H.264/AVC,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 674–687, July 2003.

[19] B. Girod, M. Kalman, Y.J. Liang, and R. Zhang, “Advances in video channel-adaptive streaming,” in Proc. ICIP 2002, Rochester, NY, Sept. 2002.

[20] Y.J. Liang and B. Girod, “Rate-distortion optimized low–latency video streaming using channel-adaptive bitstream assembly,” in Proc. ICME 2002, Lausanne, Switzerland, Aug. 2002.

[21] S.H. Kang and A. Zakhor, “Packet scheduling algorithm for wireless video streaming,” in Proc. International Packet Video Workshop 2002, Pittsburgh, PY, April 2002.

[22] M. Karczewicz and R. Kurçeren, “The SP and SI frames design for H.264/AVC,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 637–644, July 2003.

[23] S. Wenger. (September 2001). Common Conditions for wire-line, low delay IP/UDP/RTP packet loss resilient testing. VCEG-N79r1. Available: http://standard.pictel.com/ftp/video-site/0109_San/VCEG-N79r1.doc,.

[24] S. Wenger, “H.264/AVC over IP,” IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 645–656, July 2003.

[25] Y.-K. Wang, M.M. Hannuksela, V. Varsa, A. Hourunranta, and M. Gabbouj, “The error concealment feature in the H.26L test model,” in Proc. ICIP, vol. 2, pp. 729–732, Sept. 2002.

[26] Y.-K. Wang, M.M. Hannuksela, and M. Gabbouj, “Error-robust inter/intra mode selection using isolated regions,” in Proc. Int. Packet Video Workshop 2003, Apr. 2003.

[27] R. Zhang, S.L. Regunathan, and K. Rose, “Video coding with optimal inter/intra-mode switching for packet loss resilience,” IEEE JSAC, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 966–976, July 2000.

[28] S. Wenger, “Video redundancy coding in H.263+,” 1997 International Workshop on Audio-Visual Services over Packet Networks, Sept. 1997.

[29] Y.-K. Wang, M.M. Hannuksela, and M. Gabbouj, “Error resilient video coding using unequally protected key pictures,” in Proc. International Workshop VLBV03, Sept. 2003.

[30] B. Girod and N. Färber, “Feedback-based error control for mobile video transmission,” in Proc. of IEEE, vol. 97, no. 10, Oct. 1999, pp. 1707–1723.

[31] S. Fukunaga, T. Nakai, and H. Inoue, “Error resilient video coding by dynamic replacing of reference pictures,” in Proc. IEEE Globecom, vol. 3, Nov. 1996.